Demographic Transformation, Eroding Social Capital and Segregation on Outskirt Areas of Hungarian Cities

by Gábor Vasárus

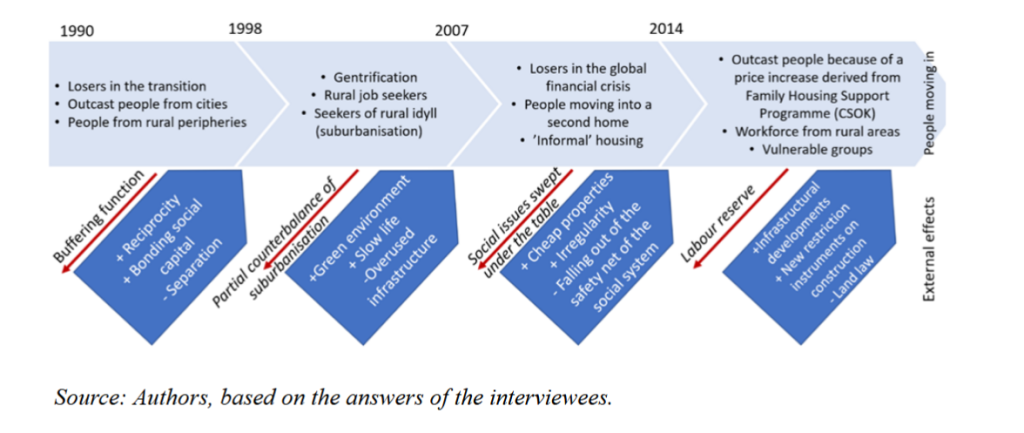

The spatial dynamics of Hungarian urban outskirts reveal a multifaceted and multi-scalar picture of segregation. While certain phases have seen a decline in micro-level segregation due to the mosaic-like arrival of new residents, sharp differentiation between neighbourhoods is becoming increasingly pronounced. Accessibility, infrastructure, and the availability of amenities shape these contrasts, leading to the coexistence of suburbanizing, affluent districts and deprived, segregating zones in close proximity—an arrangement that generates tensions resembling gentrification-like processes.

Outskirts in Hungary constitute an administratively defined category within municipal boundaries, typically encompassing the majority of the territory. Historically serving agricultural production, nature conservation, and recreation, many of these spaces—particularly allotments and vineyards—have evolved into permanently inhabited environments.

Interviews with decision-makers revealed a strong association in their discourse between segregated areas and Roma inhabitants. Yet the perspectives of social workers and NGOs, as well as our field observations, challenge this view. Instead, poverty and economic exclusion—rather than ethnicity—emerge as the key factors underpinning segregation. As one interviewee noted: “There are life situations, such as divorce, when money runs short, and people are pushed out to the outskirts. I think this process will increase in the short term.”

Segregated neighbourhoods in the outskirts are typically located in remote sections, where housing stock is in poor condition, the infrastructure underdeveloped, and access limited by unpaved roads in the winter. By contrast, accessible zones with attractive landscapes—vinehills and allotment areas—have become magnets for affluent newcomers. These dual trajectories lead to a juxtaposition of prosperity and deprivation within the same spatial frame.

Least accessible neighbourhoods attract low-income groups from both rural peripheries and declining urban areas. These settings resemble rural crisis zones in their social composition, behavioural patterns, and constrained residential choices. Yet a distinctive feature is their proximity to suburbanising zones, particularly in large vinehill and allotment districts, where both disadvantaged and affluent groups coexist, even though the physical fabric was never intended for permanent settlement.

The research underscores critical data gaps. We would like to highlight the outdated census classifications, under-registration, and inadequate recognition of marginalisation. These deficiencies hinder planning and the provision of targeted social services. In some cases, local governments have evaded responsibility, with one respondent summarising the situation: “The people living in the outskirts are basically hiding out of shame.”

Reference: Vasárus, G. , Á. Szalai, J. Lennert 2025. ‘Demographic Transformation, Eroding Social Capital and Segregation on Outskirt Areas of Hungarian Cities.’ Critical Housing Analysis 12 (1): 1-11. https://doi.org/10.13060/23362839.2025.12.1.582

Reference: Vasárus, G. , Á. Szalai, J. Lennert 2025. ‘Demographic Transformation, Eroding Social Capital and Segregation on Outskirt Areas of Hungarian Cities.’ Critical Housing Analysis 12 (1): 1-11. https://doi.org/10.13060/23362839.2025.12.1.582