New legislations and challenges in Europe:

what to do with textile waste?

Emese Dobos

From January 2025, it is mandatory to collect textile waste separately in the European Union. The big question now is what will happen to it. Companies involved in the collection and processing of textile waste in Europe are declaring insolvency one after the other, while the European Parliament has just adopted an extended producer responsibility system designed to finance their operations to some extent.

From January 2025, it is mandatory to collect textile waste separately in the European Union. The big question now is what will happen to it. Companies involved in the collection and processing of textile waste in Europe are declaring insolvency one after the other, while the European Parliament has just adopted an extended producer responsibility system designed to finance their operations to some extent.

To date, just over 20% of textile waste generated in European Union member states has been collected separately. The fate of textile waste is important because, according to the Waste Framework Directive (WFD), Member States must collect textile waste separately from 1 January 2025. It therefore follows logically that if we collect it separately, something should be done with it that is not too harmful to the environment.

According to data from the European Environment Agency (EEA), 6.95 million tonnes of textile waste were collected in the EU in 2020: this is equivalent to one person throwing away 16 kilograms of clothing per year. More than 80% of textile waste comes from consumers. More than half of the Member States had already implemented separate collection before this deadline. However, this focused on textiles that could be reused, not on items that were torn, stained or full of holes. Based on EEA data for 2020, there is a fairly large variation: while 50% of used clothing was collected separately in Belgium and Luxembourg, the figure was 2% in Bulgaria and Romania. In the case of Hungary, it seems more realistic that there is no data than the 0% reported by the statistics, as used clothing has been collected selectively in Hungary for several decades. In October 2025, the European Commission reported 12.6 million tonnes of textile waste.

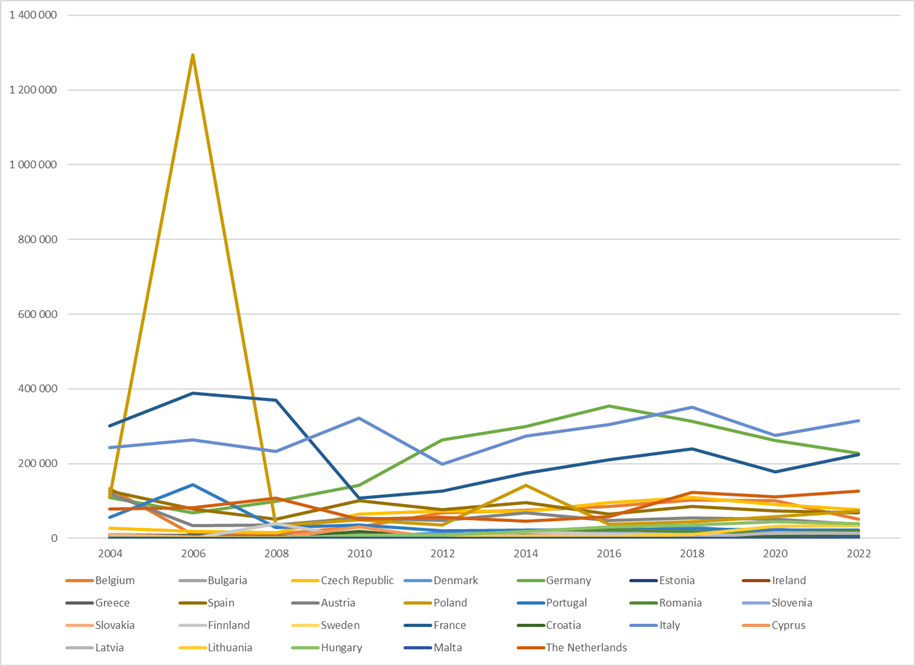

Treated textile waste (in tonnes) in European Union Member States between 2004 and 2022

Source: Eurostat

Based on Eurostat data, it is difficult to compare the amount of textile waste treated in EU Member States and its development, as data is not available for all EU Member States for all years examined, and the methodology behind the data collection is different (at least for the time being). However, it is certain that the amount of textile waste has increased since the 2000s, and its collection and treatment have presumably improved. As the figure shows, Hungary is in the middle: although the amount of textile waste treated domestically is increasing year by year, Hungarians do not throw away the most clothing in the EU. Moreover, the latest available data refers to 2022, so the exponential growth in ultra-fast fashion consumption (and the resulting waste) over the past few years is not yet reflected in these figures. Since the proportion of selectively collected textile waste has been estimated at 20% so far, even if from now on not a single pair of socks ends up in municipal waste, but everything is placed in street textile waste collection containers, the amount of collected textile waste is expected to increase at least fivefold.

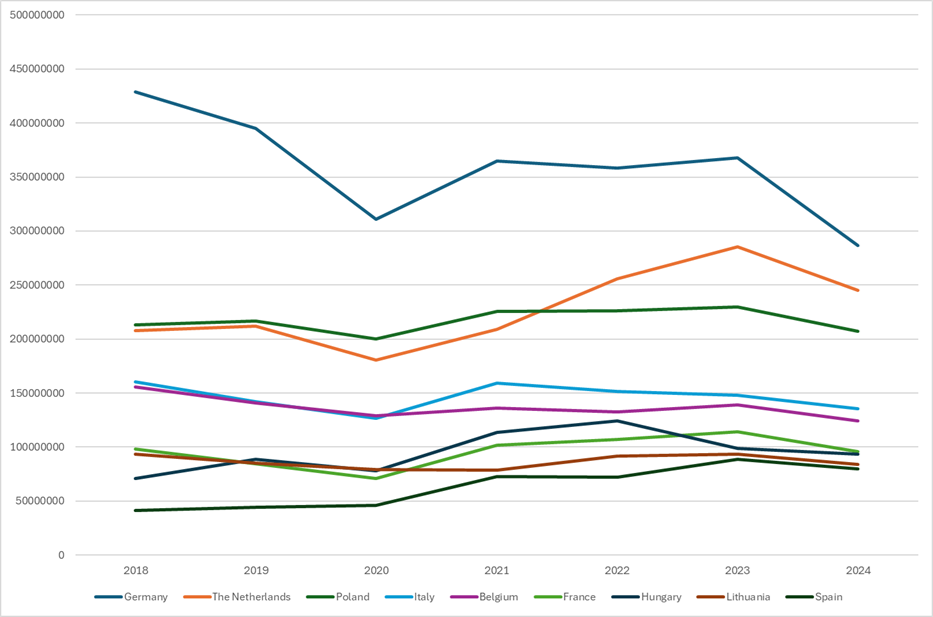

The largest EU textile waste (SITC 269) exporters and changes in export value between 2018 and 2024

data source: UN COMTRADE (value in US$)

If we look at which EU Member States export the most used clothing, Hungary ranks quite high: in terms of export value, we were seventh in 2024. However, this does not mean that we export what we collect here: companies operating in Hungary mostly import textile waste, i.e. secondary raw materials, from Western Europe, which they sort and process domestically. It would obviously be interesting to compare textile waste exports in terms of value and weight, but unfortunately, we are unable to do so because in most cases only estimated weight data is available. Between 2018 and 2024, there was a slight change in dynamics between countries, although the list of the most significant textile waste exporters remained unchanged. The general trend is that while the value of exported textile waste declined everywhere in 2020, most likely due to supply chain disruptions caused by the coronavirus pandemic, exports then increased in most countries. This declined again by 2024, but it would be too early to conclude from this that a larger proportion of waste was treated locally.

Also according to EEA data, the European Union has the capacity to store 1.5 million tonnes of textile waste per year, which is barely a fifth of the 2020 collection volume. As sorting textile waste is extremely time-consuming and mostly requires manual labour, it is mainly carried out in countries with low labour costs. However, as the EEA pointed out in a 2023 report, it is very uncertain what will happen to textile waste once it leaves the EU’s borders.

What happens to the collected textile waste?

When we talk about recycling textile products, if we think that, for example, old jumpers will be turned into T-shirts, we are very far from the truth. What actually happens to them?

- About 60% of it starts the cycle again as second-hand clothing.

- There are several ways to recycle: upcycling and textile-to-textile recycling are not feasible on an industrial scale, so downcycling comes into play to a greater extent.

- We incinerate it (or, to put it more nicely, use it for energy).

- Ultimately, it ends up in a landfill.

Although the secondary market for clothing products is undoubtedly a dynamically growing market segment, this statement also holds true for the market for high-quality, branded and luxury products. However, it is highly likely that no one wants our discarded, unwanted, ultra-fast fashion products.

One view on the export of used clothing is that sooner or later, items discarded in developed countries will end up in developing countries as actual waste. Kenya, for example, receives a huge amount of used clothing from Europe: however, as we can see, the vast majority of used clothing is of such poor quality that not only does its resale to locals provide less and less livelihood, but it also contributes directly to environmental disaster and the decline of the local textile and clothing industry. The same process, known as waste colonialism, has been observed in Accra, Ghana, and in the Atacama Desert in Chile. In June 2025, a joint investigation by Unearthed and Greenpeace Africa revealed that used clothes discarded by Europeans are piling up in nature reserves in Africa. The Ghanaian Used Clothing Traders Association, for example, takes a different view. At a conference last year, Marlvin Owusu, a member of the association, spoke about how differently Europeans and Africans view waste, and how the data circulated by various sensationalist non-profit organisations do not reflect the reality of how much of the used clothing exported to African countries is actually waste, i.e. completely unusable for other purposes. The Hungarian company Textrade Kft. also exports a lot of used clothing to African countries, but it is strictly sorted – this is not actual waste. The group is Central Europe’s largest textile sorting plant: it employs more than 500 people and sells to more than 70 countries on six continents. As Bence Hunyadi, the company’s chief operating officer, emphasised: “It’s one thing to send rubbish somewhere, but there are things that do have value.” A container of sorted used clothing is not worthless: a 28-tonne container is worth tens of thousands of euros, and shipping it costs between €3,000 and €7,000.

But is textile waste really waste? If we assume that the majority of items collected as textile waste are still in perfect condition to be reused as second-hand clothing, then the answer is clearly no. A uniform definition and regulation is important, on the one hand, for more reliable statistics and, on the other hand, because it determines the costs associated with used clothing and the options for its treatment. Before 2023, Textrade collected “used clothing”, and after the change in legislation, it collected “textile waste from the population”. While waste is not subject to customs duties, used clothing is. Although Hungarian regulations clearly define the waste status, this is still pending in the EU. However, it would be good for processing companies if a consensus were finally reached.

But why is recycling so difficult? Most clothing products are made of mixed fibres (i.e. they contain cotton and polyester, cotton and elastane, or even wool and polyamide, etc.). Even if there is a label indicating the exact composition of the material, in most cases it is cut out by the wearers. In addition, there are various threads, elastics, buttons, zippers used in the manufacture of the product, and we have no idea about the chemicals used in the manufacturing process. In a recent study, researchers at the Technical University of Denmark examined 4,000 items of clothing. Over the course of a single season, they identified 618 different raw material variants and concluded that only 2% of these were suitable for high-quality recycling. Market acceptance is not helped by the fact that, while there is no industrially scalable technology for textile-to-textile recycling (which currently accounts for 1% of global recycling), the price of crude oil is low. This makes it much cheaper to produce polyester from (virgin) crude oil than to recycle it. Which, incidentally, is made from PET bottles, not from used T-shirts, socks or trousers.

Swedish company Renewcell filed for bankruptcy in February 2024 because the fashion brands that had previously seemed enthusiastic and cooperative were unwilling to pay a premium for the company’s raw materials: just one year after they started scaled production, they were almost the only ones in the market for the industrial-scale production of so-called new-generation raw materials. The company extracted cellulose from cotton-based raw materials, from which it created a new fibre. The irony of the situation is that, due to the inefficiencies of the current European selective collection system, they also imported used clothing from Bangladesh. A few months later, however, it seemed that the company had been saved: it continued to operate under a new name and with new owners. However, according to an article published in the Stanford Social Innovation Review, there were numerous flaws in the Renewcell story, which are certainly instructive for future initiatives.

Although wool accounts for only about 1% of global textile fibre production, as most clothing products are made from polyester and cotton, industrial-scale recycling has developed in Italy, alongside Germany, Pakistan and Thailand, with a focus on wool. As reported by Bloomberg, there are more than 7,000 textile and clothing companies in Prato, many of which specialise in recycling wool products. The process is relatively simple: buttons are removed from the products by hand, they are sorted by colour, and then the products are mechanically shredded to form new fibres and yarns. There is no need for dyeing. This is how Manteco, a supplier to luxury brands, produces its fabrics, for which it currently imports mainly unworn wool knitted sweaters from the US.

According to a report published by the Boston Consulting Group in August 2025, textile waste recycling could exceed 30%, while the circular textile industry could create 180,000 new jobs annually and generate $50 billion worth of raw materials. According to an earlier report by McKinsey, new fibres could be created from 18-26 per cent of textile waste. A report by Sorting for Circularity Europe, which brings together European collection companies, also points to the enormous potential of textile waste recycling. At the same time, most reports acknowledge that recycling is currently costly and limited, and recycled raw materials are correspondingly more expensive. However, they do not consider whether it actually makes sense to spend a lot of money on producing recycled raw materials, only for the wearer to discard the product made from them within a short period of time.

Existing companies – on the brink of collapse?

According to previous literature, there are 17 textile recycling companies in Europe: together, they can recycle approximately 1.3 million tonnes per year, mostly by a mechanical method. This means that textile waste, like wool, is essentially shredded and turned into rags or insulation material. The British charity WRAP has created a database listing textile sorting, pre-processing, recycling and yarn manufacturing companies and charities that accept donations in the EU and the United Kingdom. According to the latest update in February 2024, more than 200 entities are involved in this field, many of which are still in the pilot phase.

The problem is that textile recycling has not been the sector with the greatest economic potential so far. While the volume of textile waste has increased significantly in recent years due to fast and ultra-fast fashion products, its quality has deteriorated considerably. Le Relais, the leading French textile waste collection company, stopped collecting waste in the summer of 2025: in 2024, they received €156 per tonne in government support to offset their losses. In 2026, this would be increased to €223. In protest, in June 2025, Decathlon and Kiabo stores were covered in waste to draw attention to the chronic underfunding of the sector and the lack of government support.

Several leading European companies, Texaid and Tell-tex, have previously reported that they are barely able to cover their operating costs. Texaid, one of the largest European textile recycling companies, which has been operating for 45 years, handles 70,000 tonnes of textile waste annually and employs more than 1,000 people. It has sorting plants in Hungary, Germany and Bulgaria. At their Hungarian subsidiary in Bélapátfalva, which has been operating since 2008, 80 employees inspect and sort 3,600 tonnes of used clothing annually. The company reported insolvency in June 2025. The Soex Group, one of the five largest European textile collection, sorting and processing companies, announced its insolvency in October 2024. Soex processes 80,000 tonnes of textile waste annually. However, the initiation of proceedings does not yet mean the company is bankrupt: they are currently looking for new investors and working on restructuring the company. The Salvation Army, one of the biggest collector of textile waste in the UK also announced the pause of their operation at the beginning of December 2025.

Textrade Kft. is the market leader in textile waste collection and processing in Hungary. The company began collecting used clothing shortly after its launch in the 1990s, and the container system was launched around 2005. The company is a subcontractor of MOHU, the organisation responsible for concession waste management, and as Bence Hunyadi, the company’s chief operating officer, pointed out, “the collection itself is quite a deficit operation.” Textrade currently sorts 35,000 tonnes of textile waste per year, more than half of which is still perfectly wearable and continues its “life” as used clothing. The company has a larger capacity than this, so it can process more used clothing. There are several processing companies operating in Hungary: TESA Kft. in Mohács produces materials for industrial use, while Temaforg Zrt. in Kunszentmiklós manufactures geotextiles, so Hungary has both the capacity and the experience.

Will extended producer responsibility be the solution?

As part of the 2023 review of the Waste Framework Directive, the European Commission has proposed harmonised extended producer responsibility (EPR) regulations for the textile industry. The European Commission has proposed that a significant portion of the EPR contributions paid by textile manufacturers and retailers be spent on waste prevention measures and preparing products for reuse. This was previously introduced in France, Hungary and the Netherlands, and operated on a voluntary basis in Belgium. (In Hungary, the extended producer responsibility fee payable by manufacturers is 145 HUF/kg for textile products.) As a latest step, the European Parliament adopted the EPR revision in September 2025. This means that Member States have 30 months to set up national systems, so it will start across the EU in 2028 at the earliest. Under this framework, manufacturers must contribute financially to the fate of their products once they are no longer in use, regardless of whether they are e-retailers and whether their businesses are based in the EU. Companies involved in collection, processing and recycling will receive a stable income from this, which they can use to increase and develop their existing capacities, invest in automated solutions, and so on.

However, the problem with the current system is that:

- It has been widely criticised because the EPR fees imposed do not even come close to covering the costs of sorting, processing and treating textile waste, and

- if textile waste is exported outside the EU (which is the case for a large percentage of it), it is precisely the developing countries that do not benefit from the EPR revenue, where it is highly likely that not only is there no efficient technology and possibly insufficient capacity for recycling, but the waste management infrastructure is fundamentally less developed than in the EU.

- Critics of the current EPR argue that manufacturers will simply raise prices so that users ultimately pay for the cost of collecting and processing the products.

- As textile waste is rarely collected, processed and recycled within national borders, the slow harmonisation of the EPR system also complicates EU processes.

Although this concept is not on the agenda of decision-makers to my knowledge, in theory, the concept of ultimate producer responsibility was originally proposed to overcome these challenges in relation to e-waste, which would entail extensive traceability and greater accountability for all manufacturers and distributors.

There is no shortage of coalitions at the moment. While upcoming regulations also require manufacturers to use recycled raw materials in the EU market, Rehubs, the industry coalition, published a relatively simple action plan in September 2025, listing the steps needed to establish fibre-to-fibre textile recycling in Europe. If they succeed in centralising the currently highly fragmented processes and securing €5-6 billion in investment over the next seven years, they plan to recycle 2.5 million tonnes of textile waste by 2032 – still only about one-third of the volume collected. Twelve textile companies established the European Circular Textile Coalition in October 2025 and are also asking the EU to match their ambition with investment. One of their key priorities is to develop a circular infrastructure based on regional, short supply chains, which would reduce the need to import textile waste and enable high-quality recycling through proper sorting.

So, what will happen to textile waste?

Although the new EPR regulation is intended to remedy the situation by requiring brands and retailers to contribute financially to the costs of dealing with end-of-life products, it is highly unlikely that the amount collected will cover the costs of disposing of or processing textile waste. Obviously, high-quality textile waste could be used to produce suitable recycled raw materials, but the question remains as to what to do with the majority of waste, which consists of cheap, quickly discarded products that are mostly synthetic and made of mixed fibres. As recycled raw materials are currently more expensive and available in much smaller quantities, market forces do not encourage fashion companies to use them.

Although the European Union has already taken up the fight against ultra-fast fashion products, EU economic ministers have already reached an initial agreement to end duty-free shipments from outside the EU costing less than €150. However, regulation is only one side of the coin: there is also an urgent need to change attitudes. Obviously, the solution would be for people to buy much less. What is needed is for people to wear the things they buy for as long as possible and to repair them, if necessary. But this goes completely against the nature of fashion consumption. At the same time, even if people were willing and able to have items repaired, many are put off by the fact that it can sometimes take a lot of research to find a good shoemaker, for example, and not many people take their coats to a seamstress to have the zipper replaced if the repair costs about the same as buying a new one. And it is not that the seamstress doing the repair is too expensive: new products are dangerously cheap.

It is clear that the European Union cannot continue the practice of simply importing waste, i.e. secondary raw materials, which, let’s be honest, where they do not know what to do with. The EU has been slow to act and is currently completely unprepared to deal with the almost incomprehensible amount of textile waste generated in its Member States, which will sooner or later have to be collected in larger quantities. What is certain, however, is that we need to think in terms of shorter supply chains: sorting the largest possible proportion of collected textile waste as efficiently as possible will significantly reduce the import needs of European textile waste processors. Good solutions must be properly incentivised. And if we look at the backtracking by EU decision-makers on due diligence, sustainability reporting and supply chain transparency (obviously due to corporate lobbying), it would not be surprising if, at the end of the day, the European Union were to soften its stance, relax its regulations, extend deadlines and make generous exceptions.